Guest post by Sarah Gerhardt

When people ask about gardening tools, they are often hoping for a definitive list: the best secateurs, the best spade, the best rake. The reality is that tools are extremely personal.

Your choice of tools depends on the kind of work you do, where you work, your physicality and any limitations. It is also shaped by small practical decisions: how you carry your tools, how well you maintain them, and how much repair you are willing or able to do.

As a professional gardener, the tools I rely on are those that have proved themselves over time. They are a mix of affordable and higher-end options that can withstand daily use and feel intuitive after hours of work.

The tools featured in this blog post are exclusively hand tools, because they make up around 90 percent of what I use daily. As an inner-city gardener working mainly in private gardens, I rarely need power tools. Add limited parking in a city like Edinburgh, and my bike is often my primary mode of transport.

People underestimate how much you can carry in a good pair of panniers, but you still have to be selective. Gardening by bike has clear environmental benefits over petrol-powered transport and tools, but it also sharpens your judgment: only tools that genuinely earn their weight make it into regular rotation.

I am fairly strong but relatively short, with small hands. That means weight, grip size, and balance matter to me more than sheer robustness. Tools that are awkward to handle or cause fatigue too quickly simply do not earn a place in my regular kit.

This is not a list of the “best” gardening tools in any absolute sense. It is an account of what I actually use, why, and what I have learned from tools that have failed me as well as those that have lasted. Where brand names appear, it is because design and build quality genuinely affect performance over years of use, not because there is a single correct answer. Other gardeners will reasonably make different choices, and part of becoming confident in your own practice is understanding why.

If there is a single principle running through all of these tools, it is this: the right tool, used properly, makes gardening not only more efficient, but more sustainable in the long term.

Secateurs: the tool you should not cheap out on

Secateurs are the tool I would always prioritise spending money on. They are the implement most gardeners use most often, and small differences in design, balance, and durability add up over the years.

I reach for Felco secateurs by default, specifically the classic No.2 model. They are robust, fully repairable, and replacement parts are easy to source in the UK. I also strongly prefer the thumb catch on Felcos, which allows me to lock and unlock the secateurs one-handed. That may sound like a minor detail, but when you are pruning continuously, ease of operation matters.

I always go for bypass secateurs, which make clean cuts without crushing plant tissue. Anvil secateurs can compress and damage branches. Interestingly, the Felco No.2s combine a bypass action with a reinforced edge that handles slightly tougher material than pure bypass secateurs, without sacrificing the clean scissor-like cut.

As a backup, I have a pair of Gardena secateurs. I like them because they are cheaper and slightly lighter, but I had an internal spring break after a few months of intensive use, and sourcing a replacement part in the UK was tricky. Unlike the all-metal Felcos, Gardena secateurs incorporate plastic components, making them lighter but less long-lived. They are a reasonable option at the lower price point, but not my first choice for heavy daily use. Felcos cost roughly £ 40-70 without a discount; Gardena models around £15-40.

High-quality Japanese secateurs, like Okatsune or Niwaki, are widely respected. Their simple, precise design with fewer parts reduces failure points. At a previous workplace, I was issued Okatsunes but swapped them for Felcos after several months. I found the handle-mounted locking catch of the Okatsunes less intuitive, particularly when working one-handed.

That said, some gardeners strongly prefer the straightforward catch on the Okatsunes and Niwakis over Felco’s more elaborate thumb mechanism, which can seize or loosen if poorly maintained. Okatsunes are priced similarly to Felcos; Niwakis range from £40 to £160.

Whichever brand you choose, invest in the best secateurs you can reasonably afford. If the budget is tight, wait for a sale. A sharp, comfortable pair of secateurs will do more for your gardening than almost any other purchase.

Whenever possible, handle secateurs in person before buying. Grip, balance, and locking mechanisms are highly individual. Specialist suppliers like World of Secateurs stock a wide range, but local garden centres and tool shops remain invaluable for trying out tools.

Maintain your secateurs well: sharpen before use, clean after, store dry, and periodically disassemble if possible. Familiarity with the mechanism makes future repairs far less daunting.

Loppers: the bridge between secateurs and saws

For medium-tick branches that are too large for secateurs but awkward to approach with a saw, I use extendable (technically “telescopic”) bypass loppers. My current pair is a set of Fiskars 112120, capable of cutting branches up to 32 mm in diameter, a model that has sadly been discontinued.

I tend to choose Fiskars because they offer good mid-range cutting tools that are often lightweight and relatively durable, striking a balance between comfort and reliability for daily use. I prefer extendable loppers because they increase my reach and reduce the need to use a ladder, which is especially helpful as a relatively short gardener.

The pair I currently use is a second-hand set that I reinstated after it had been stored poorly and developed surface rust. Over time, it appears to have developed a minor fault that affects the cut quality a bit. By contrast, the same model I used for many years at a previous workplace always cut flawlessly when well maintained. I have tried the successor model, the Fiskars L86, as well as options from other brands, but none felt quite right: some were too heavy, others were not extendable, and a few could not handle the branch diameters I encounter most frequently.

If I cannot find a suitable replacement, I will likely invest in a non-extendable pair in the future. Even with its current quirks, the 112120s remain practical: reach and leverage matter, and they make cutting medium branches far easier than forcing a saw into awkward positions. When a precise cut is critical, I still reach for secateurs or a pruning saw.

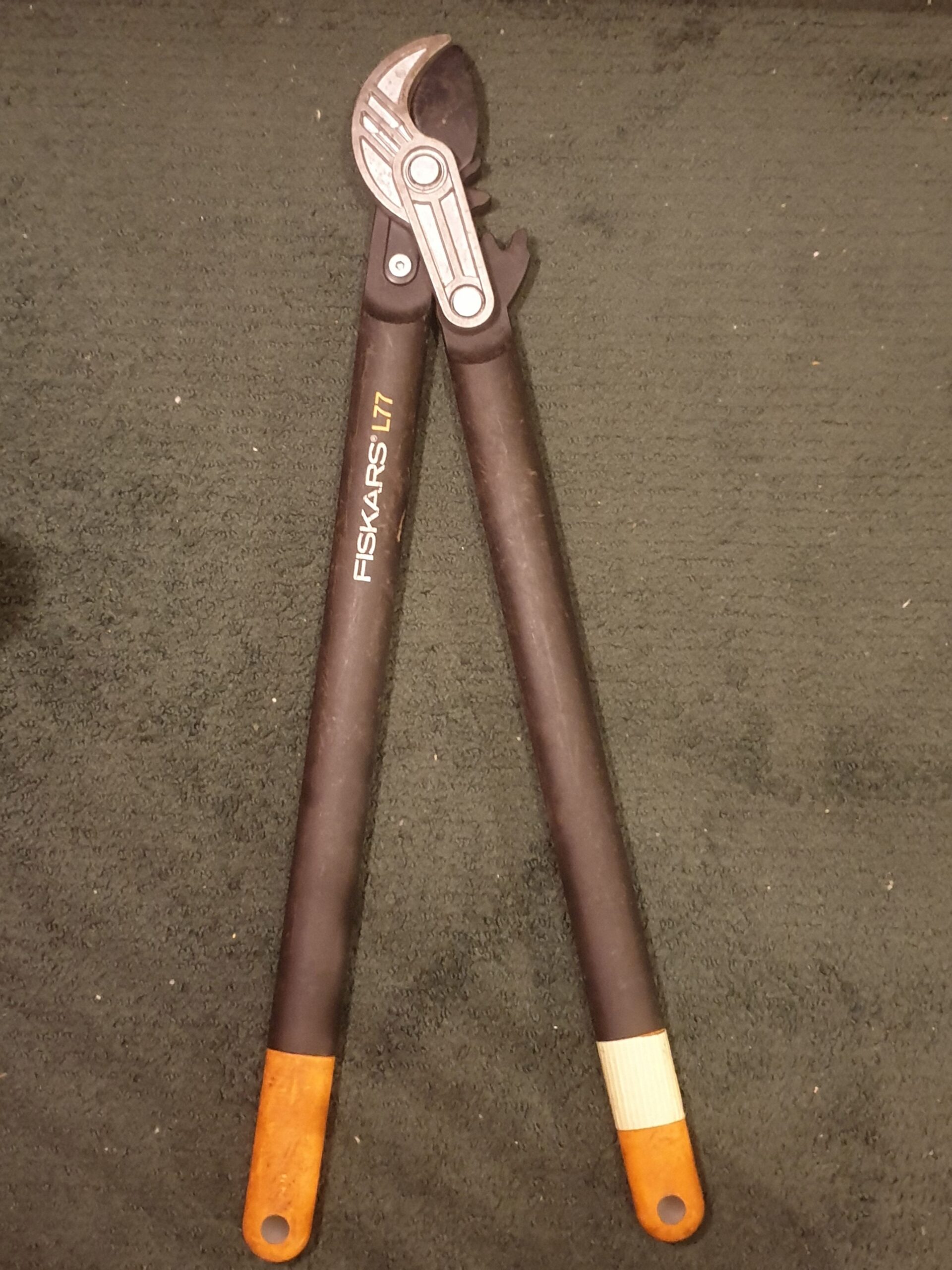

I also keep a pair of Fiskars L77 anvil loppers for chopping up pruned material. They are lightweight, strong, and very comfortable to use, with a maximum cutting capacity of up to 50 mm. These loppers are intended for material where precision is secondary, such as dead wood or branches that have already been pruned.

This section of my toolkit illustrates a recurring theme: technique, judgement, and understanding a tool’s strengths matter far more than brute force or having the “perfect” implement.

Pruning saw: can take down a small tree if need be

When pruning exceeds around 32 mm in diameter, I reach for my pruning saw. Again, Fiskars is my go-to brand here. I use the mid-range Fiskars SW75, which has a usable blade length of 220mm.

Its main advantage is compactness. The blade retracts fully into the handle, making it safe to carry, and it takes up very little space in my tool bag. It also comes with a belt clip, which is extremely useful when working inside shrubs and switching frequently between tools.

Despite its modest size, this saw is capable of far more than many people expect. I have taken down trees of considerable size and trunk width using only the SW75, a rope and careful technique. On occasion, gardeners who rely heavily on power tools will smile condescendingly at the female gardener with the small pruning saw, not realising that, in the right hands, it can replace a chainsaw for certain tasks. Silky’s Ibuki pruning saw, for example, is often marketed as a “genuine alternative to using a small chainsaw – a little more effort, but more peaceful, with no fuel cost and much more rewarding.”

The SW75 cuts on the draw, like most pruning saws, meaning it is designed to cut as you pull rather than push. This requires less effort from the user and allows for a cleaner cut. Some users report breaking the handle of the SW75, but in my experience, this is usually the result of pushing the saw or using excessive force rather than letting the teeth do the work.

The main disadvantage of the SW75 is that the blade cannot easily be sharpened. The hardened teeth retain their sharpness for a long time, but effectively make the saw disposable once it goes blunt, as the saw blade cannot be replaced either. I replace my SW75 roughly once a year. At around £35, this is financially manageable, though it does feel wasteful. Some gardeners do manage to sharpen these blades with a diamond file, but it requires a lot of time and patience.

I have been considering upgrading to a sharpenable Silky saw, such as the Sugoi or Ibuki, which aligns more closely with my preference for long-lasting tools. At around £100, however, it is a significant investment – and not one I want to leave accidentally buried in a compost heap.

A pruning saw looks deceptively simple to use, but it is important to use it correctly both for the longevity of the saw and the health of the plant that the saw is being used on. I already mentioned that pressure should only be applied when pulling, not when pushing. When cutting off larger tree branches, it is important to use the three-cut method to reduce tearing of the bark or damaging the branch collar, the thickened area at the base of the branch where it joins the tree trunk.

I use this technique whenever I cannot easily control the weight of the material as I cut. The first cut I make is an undercut around 20 cm above the point where my final cut will be. This final point is usually just outside the branch collar. The undercut only needs to go partway through the branch. It helps to make it a V-shaped notch on larger branches.

Next, I make a second cut from above, a few centimetres further out from the branch collar than the undercut. This cut goes all the way through. When the weight of the branch is released, the undercut prevents the bark from tearing down the trunk.

At this point, you are left with a short, uneven stump. This can then be removed with a clean, controlled final cut just outside the branch collar, allowing the plant to heal properly.

For particularly large or heavy branches, I will often begin with a reduction cut higher up to reduce the overall size and weight before using the three-cut method. This makes the process safer, more controlled, and far less stressful for both the gardener and the plant.

Conclusion

The tools I introduced in this post are my personal choices. Over time, I have learned that good gardening is less about owning certain equipment or having a certain physicality and more about understanding what a tool is designed to do, how to use it, what works for you, and when to stop and change approach.

I hope you enjoyed part 1 of my mini series and found something useful to take away for your own gardening practice. In future posts, I will look at the digging tools I rely on, as well as some less obvious but indispensable pieces of kit that make working efficiently much easier, particularly as a mostly bike-based gardener.

About the author: Sarah Gerhardt is a gardener, linguist and punk musician based in Edinburgh. She was head gardener at the Dean Gardens, Edinburgh for 9 years and runs her own gardening business Gerhardt’s Garden Service. Find out more via her Linktree: https://linktr.ee/gerhardtsgardenservice